This article, "CECL Encounters a ‘Perfect Storm’," originally appeared on CPAJournal.com.

After years of deliberation and comment, FASB’s long-awaited standard on accounting for credit losses, in the form of ASU 2016-13, was finally issued in 2016 and became effective in 2020. The implementation of this complex and controversial standard has coincided with the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic and historical macroeconomic uncertainty—a “perfect storm” of factors. This article reviews recent disclosures to analyze the impact the new guidance has had on reporting for credit losses.

***

After a long developmental process, in June 2016 the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) issued Accounting Standards Update (ASU) 2016-13, Financial Instruments–Credit Losses (Topic 326), which represented a significant change in the financial accounting model for credit losses applicable to all financial instruments other than those measured at fair value. The new standard recently became effective for fiscal years beginning after December 15, 2019, which coincides with the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. The authors, in a prior article (Arianna Pinello and Ernest Lee Puschaver, “Accounting for Credit Losses under ASU 2016-13: Anticipating the Impact on Reporting and Disclosure,” The CPA Journal, February 2018), reviewed 2016 Form 10-K disclosures to provide insight into the impact the ASU was expected to have upon implementation. One of the key attributes of ASU 2016-13 is that implementation calculations reflect the macroeconomic environment at the time of adoption. Given that ASU 2016-13 is being adopted and implemented at a time of unprecedented social and economic uncertainty due to the COVID-19 crisis, its implementation could be assumed to be especially challenging. The authors present a review of current expected credit loss (CECL) disclosures in 2018 and 2019 Form 10-Ks as well as first-quarter 2020 earnings releases and Form 10-Qs. The findings indicate how an unforeseen public health crisis, severe macroeconomic uncertainty, and the inherent complexity of the guidance—a veritable “perfect storm” of factors—has affected the implementation impact of ASU 2016-13.

Challenges of ASU 2016-13

ASU 2016-13 requires that CECL be recognized for credit losses applicable to all financial instruments other than those measured at fair value, in a departure from the previous “incurred-loss” model. CECL assessments consider not only realization issues related to a particular credit, but also the overall macroeconomic situation, as well as historical experience. Subsequent to initial recording, CECLs are adjusted each reporting period for changes in those estimates.

Adoption of the ASU was expected to generate a cumulative charge to retaining earnings under its required modified retrospective method; this expectation was confirmed by subsequent reviews of 2019 Form 10-Ks and first-quarter 2020 information. An increase to the allowance for credit losses (ACL) was expected because, by its nature, ASU 2016-13 strives to be more forward-looking in an effort to overcome the perceived lagging of loss recognition that occurred under the incurred-loss model (John Page and Paul Hooper, “The Fundamentals of Bank Accounting: Its Effect on Current Financial System Uncertainty,” The CPA Journal, March 2013, pp. 46–52). One of the biggest challenges of the guidance is that the underlying valuations and estimations that drive CECL analyses are a function of not only the nature of the credit portfolio, but also of the macroeconomic environment prevailing at the time the estimations are reported. Therefore, by design, any uncertainties entrenched in the macroeconomic environment at the time of reporting are embedded in CECL estimations by default.

Under SEC Staff Accounting Bulletin (SAB) 74 (Disclosure of the Impact that Recently Issued Accounting Standards Will Have on the Financial Statements of the Registrant When Adopted in a Future Period), SEC registrants are required to disclose in their Form 10-Ks the anticipated financial statement impact that newly issued accounting standards are expected to have when implemented on a future date. Because the ASU represented a major change in the financial accounting model for credit losses and significantly raised the complexity of the estimation process, implementation of the ASU was universally anticipated to be a very significant project that would take years to fully establish the underlying analytics, procedures, methods, and policies.

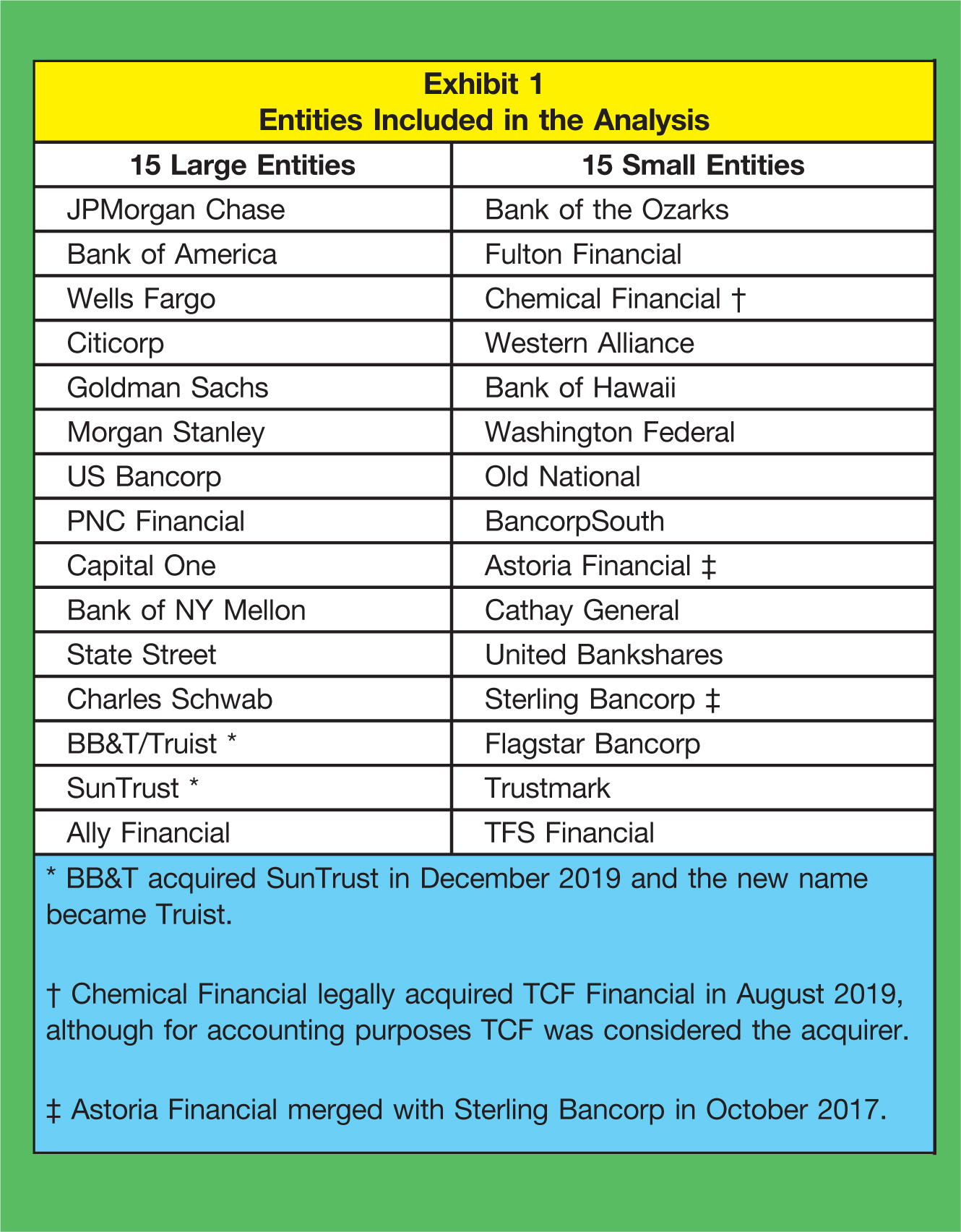

As reported in Pinello and Puschaver’s previous analysis of 2016 Form 10-K filings of 15 large and 15 small banks (see Exhibit 1 for a list of entities included in the sample), entities’ initial disclosures discussed the difficulty of analyzing the new standard, the significant management resources that needed to be marshaled, the need to use external consultants, and the development of new systems to meet the requirements of the new ASU. While reporting entities’ 2016 Form 10-Ks were not generally expressive about the likely impact of the new standard, it is noteworthy that, even at that time, 9 of the 30 entities sampled had already chosen to disclose some form of commentary along the lines that the ASU was likely going to be a “material” matter.

Exhibit 1

Entities Included in the Analysis

Progression of the Adoption Process in 2018

To garner insight about the progression of the adoption process, the authors reviewed 2018 Form 10-Ks of the same 15 large and 15 small banks examined earlier and listed in Exhibit 1. While the ASU is effective for fiscal years beginning after December 15, 2019 (i.e., January 1, 2020), early adoption was permitted for fiscal years beginning after December 15, 2018. Because the underlying nature of adopting the ASU would generally result in a charge through retained earnings, it was widely predicted that companies would likely not adopt early. In addition to the initial adoption charge to retained earnings, the downside of adopting early is that a 2019 income statement loss could be reported that would otherwise have been part of the overall initial adoption charge to retained earnings. A review of the 2018 Form 10-Ks confirmed that none of the sampled entities adopted the ASU early.

In their 2018 Form 10-Ks, eight entities identified the use of third-party consultants or software vendors to assist management with adoption of the ASU. Fewer entities had identified such planned use of third-party consultants or software vendors in their 2016 10-Ks, suggesting that the implementation process turned out to be more complex than was initially anticipated. Most of the sampled entities commented about viewing their credit portfolios as comprising various segments, each requiring a different analytical commitment and extensive use of modeling. For example, JPMorgan Chase disclosed: “The firm currently intends to estimate losses over a two-year forecast period using the weighted average of a range of macroeconomic scenarios (established on a firmwide basis), and then revert to longer-term historical loss experience to estimate losses over more extended periods.”

Disclosures from 2018 Form 10-Ks reveal that management teams are reluctant to turn the CECL analysis into a mere formula-driven process—as they should not, arguably, as the financial statements and required estimates are ultimately a management estimating function, not just a mathematical exercise. As JPMorgan Chase summarized in its disclosure: “The ultimate impact will depend upon the nature and characteristics of the Firm’s portfolio at the adoption date, the macroeconomic conditions and forecasts at that date, and other management judgments.” [emphasis added]

One would have expected that by the end of 2018, with only one year to go before required adoption, management teams would have determined whether the impact was likely to be material and what the dollar range was likely to be. But this was not evident in the 2018 disclosures. The great majority of entities were silent or noncommittal concerning the expected impact, or commented that “it depends on conditions at the time of adoption,” and thus did not present any commentary related to materiality. In six instances, management used the term “unable” and one entity used the term “not yet” while being silent about the expected impact. Such wording can have two dimensions. First, because the impact would depend upon conditions at the time of adoption, management is being noncommittal. In other instances, perhaps the underlying development and analyses were not near enough to completion. Most entities gave indications of their current status and time frames for finalizing the implementation, often using wording similar to: “We have finished development of the analytical models and will begin testing in parallel with existing processes during the latter part of 2019.” Many others, however, used such phrases as “continuing to assess and evaluate.” Only two entities actually disclosed a quantified amount for the expected impact: JPMorgan Chase disclosed a potential increase in ACL of $4–$6 billion, noting that a large part would come from its credit card portfolio. Citigroup disclosed that its expected credit loss reserves would increase by 10–20%.

One would have expected that by the end of 2018, management teams would have determined whether the impact was likely to be material and what the dollar range was likely to be. But this was not evident.

Analysis of Adoption Results

In 2019, the economic environment stayed stable as management teams sought to finalize their methodologies for the required analyses. The fourth quarter 2019 loss provisions represented 20–30% of the total annual provisions, indicating nothing unusual was foreseen on the horizon. To gain insight into the adoption impact, the authors reviewed the sampled entities’ impact disclosures reported in 2019 Form 10-Ks, and garnered more detailed information when necessary from first quarter 2020 earnings releases and Form 10-Qs. Review of these disclosures evidenced varying degrees of impact from CECL implementation, and the pattern was different for the largest entities compared to the smallest. Each entity has a unique credit portfolio, and loss experience and management judgments can vary while still conforming to GAAP. Nevertheless, one rough measure of conservatism often embraced is to consider the ACL level compared to the current year’s provision for credit losses, thereby assessing how many years of losses or degree of uncertainty it might be addressing.

In their 2019 Form 10-Ks, the last year before required CECL adoption, the ACL-to-provision ratio for the larger entities ranged from a low of 1.16× for Capital One, an entity with significant credit card operations, to 3.89× for Wells Fargo. Among the smaller entities, there was much greater conservatism evident, including more pronounced instances of provisioning reversals. Sterling was the lowest at 2.30×; at the other extreme were Old National at 11.00× and BancorpSouth, which reported an ACL of $119 million compared to a $1.5 million 2019 provision (79.33×).

The 2019 Form 10-Ks disclosed adoption results for the largest institutions generally in a range of a 30–40% increase to the ACL. Ally Financial, which has significant automobile lending activities and one of the lower ACL coverage ratios compared to its 2019 provision, recorded a 103% adoption increase to its ACL and a further increase to 157% with its first quarter 2020 provisioning. Wells Fargo, which early in 2016 alerted that CECL implementation could be material, actually disclosed a 12% reduction in its 2019 Form 10-K. JPMorgan disclosed an aggregate increase of $4.3 billion (or 33%) in its 2019 Form 10-K, which was within its previously disclosed range, reflecting an increase of $5.5 billion for its credit card operations as predicted, but also a reduction of $1.4 billion for its wholesale lending portfolio. Citigroup experienced a 29% increase to its ACL as disclosed in its 2019 Form 10-K, which was higher than the range previously disclosed. PNC Financial’s $661 million adoption charge included 27% for unfunded commitments.

This time, the economic contraction is different—it is not the normal ebb and flow of a business cycle.

The smaller entities presented much more diverse results. Two of the entities, Washington Federal and TFS Financial, have September 30 fiscal year-ends and did not have to adopt at January 1, 2020. Interestingly, both have been reporting provision reversals for the past three years, indicating very conservative ACL levels, and yet disclosed that they expect adopting CECL will still require an increase to their ACLs. BancorpSouth, which as noted above had an ACL significantly greater than its 2019 annual provision, still disclosed that adopting CECL increased its ACL by $63 million or 53%, while noting that $23 million was due to the “gross-up” for previously purchased credit-deteriorated loans.

As can be inferred from a review of their 2018 Form 10-Ks, eight smaller entities had not yet finished their analyses and, in their 2019 Form 10-Ks, disclosed a range either using percentage terms or dollar figures of what the adoption charge was likely to be. Cathay General did not adopt and said that it was “not yet able to disclose the quantitative effect.” For those entities that had not finalized an amount, management would be challenged to maintain objectivity as to what the adoption charge should be at January 1, 2020, when considering the turmoil that unfolded during the first quarter of 2020. It is refreshing to note from sub-sequent first-quarter 2020 disclosures, however, that they adopted generally within their disclosed ranges, and there did not seem to be a pattern of skewing toward the higher end of the range to take undue advantage of the retained earnings implementation charge.

Conversely, United Bankshares had estimated a range of 20–30% in its 2019 Form 10-K, but adoption actually increased its year-end ACL by 74% and, together with a larger first-quarter 2020 provision of $27 million compared to $6 million in the fourth quarter of 2019, its quarter-end ACL more than doubled. On the other hand, Cathay General opted not to adopt CECL, citing a deferral option provided under the Coronavirus, Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act (CARES) and saying it would adopt at the earlier of when the U.S. government declares an end to the national emergency or December 31, 2020. Yet under the “incurred loss” accounting model, Cathay General still reported a first-quarter 2020 loss provision of $25 million, which increased its ACL by 20% compared to three straight years of provision reversals, and it disclosed that nonperforming loans had increased by 24% since 2019 year-end. In addition, in its Form 10-Q, Cathay General disclosed adoption would likely increase its ACL by $20–$25 million and would result in an additional first-quarter 2020 provisioning of $5–$10 million.

In contrast, Washington Federal, although not required to adopt until October 1, 2020, due to its September 30 fiscal year-end, disclosed in its March 31 quarterly information that management is considering early adoption, which would date back to October 1, 2019, in order to improve its comparability with other banks. Sterling Bancorp, which has had several mergers, ended 2019 with an ACL of $106 million, then disclosed in first quarter 2020 that its ACL increased by an adoption charge of $68 million plus $22 million for “gross up from purchase credit impaired loans.” It then recorded a first-quarter 2020 provision of $137 million compared to a fourth-quarter 2019 provision of $11 million, meaning that, altogether its ACL tripled from $106 million to $326 million. Truist—which resulted from the December 2019 merger of SunTrust with BB&T—had a similar experience, as it reported a 2019 year-end ACL of $1,889 million, then an adoption increase of $3,101 million. Then, with a first-quarter 2020 provision of $893 million, it increased its ACL to $5,611 million.

Of additional note, the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) recently enacted Auditing Standard (AS) 3101 (“The Auditor’s Report on an Audit of Financial Statements When the Auditor Expresses an Unqualified Opinion,” 2017), a new auditor reporting requirement to discuss critical audit matters (CAM) in the auditor’s report. For the sampled entities, AS 3101 became effective for audits of fiscal years ending on or after June 30, 2019. The auditors universally highlighted the ACL as a CAM except in four instances (Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, State Street, and Charles Schwab), for which the ACL is presumed to be a relatively minor matter relative to their overall operations.

Unprecedented Economic Uncertainty Due to COVID-19

Incredibly, just 90 days after the required adoption date of ASU 2016-13, as management addressed finalizing adoption and recording the first quarter 2020 credit loss provisioning under CECL, the world’s economies—with the United States very much impacted—were contending with the COVID-19 crisis and the resulting economic stagnation as businesses were shut down and populations were advised to shelter in place, practice social distancing, and avoid gathering in groups. Notably, the price of oil dropped precipitously, which had a severe impact on the world’s economies. Initially, the price drop was due to price competitiveness among disagreeing OPEC members, but then it dropped significantly more because demand fell as automobile driving and airline travel shrunk dramatically.

This time, the economic contraction is different—it is not the normal ebb and flow of a business cycle. The U.S. economy had been performing well before COVID-19 entered the picture. Experts determined that the virus was very contagious and dangerous with an unsettling mortality rate. Similar to other countries, the governmental solution in the United States was to create social distancing in affected areas to decrease the virus’s rate and range of spread and avoid overwhelming the medical infrastructure. In essence, governments ordered a functioning economy to largely “shut down” with the goal of “restarting” it after the virus had been contained. Unemployment surged to over 30 million claims in just a few weeks, to levels not seen since the Great Depression, and first-quarter GDP contracted by more than 4%. Dire forecasts are abundant with a wide disparity of views. The Wall Street Journal (“Lockdown Causes Big Decline in American Output,” April 6, 2020, p. A1) reported: “At least one-quarter of the U.S. economy has suddenly gone idle… while 8 in 10 U.S. counties are under lockdown orders, according to Moody’s, they represent nearly 96% of national output.”

In response, the government is proactively trying something innovative—trying to keep workers “in place” and businesses viable, ready to swing into action when the “restart button” is pushed—something that has never been tried before. The federal government has committed trillions of dollars to supplement the populace and the economy—concurrent with the shutdown—without the normal policy lag experienced in response to, for example, the Great Depression or the 2008/09 Great Recession. The money is being committed right as the shutdown occurs in order to stabilize the economy and especially the small business sector, which is generally considered to represent 50% of the labor force. Small businesses are being granted government funding to keep employees on their payrolls with a pledge to forgive the loans when the economy restarts through the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). The private sector has been asked to accommodate the “pause” by granting waivers on consumer debt payments for mortgages and credit cards.

Although this massive government effort will undoubtedly be difficult, the overall posturing is to endure the slowdown beginning at the end of first quarter 2020 and the likely significant GDP contraction in the second quarter, with the aim of inducing some degree of meaningful recovery in the third and fourth quarters, and having the economy functioning something akin to a “new normal” by year-end.

Implementing CECL in a ‘Perfect Storm’

Management is now faced with a truly Herculean task—how to discern what is the “best loss estimate” given all the current social disruption, the economic unknowns, and political uncertainty. Meeting CECL’s requirements for macroeconomic considerations and utilizing historical experience seems impossible when, as the Wall Street Journal noted: “The root problem is that the scale of the coming default wave is impossible to assess” (“Banks Have Nowhere to Hide,” “Heard on the Street,” March 20, 2020, p. B12; “Banks Can Only Guess at Virus Fallout,” “Heard on the Street,” April 15, 2020, p. B12).

The general consensus seems to be that the second quarter 2020 results will reflect the dire economic consequences of the pandemic. But subsequently, given all the economic support and stimulus being injected by the federal government, there is a sense that the latter half of the year might experience a recovery. Yet CECL is very much a balance sheet analysis to be performed at a reporting date and the underlying basis of financial reporting is often considered to embrace a convention of conservatism. Which should carry more weight in an analysis—the near term view of a severe decline, or the longer term view that the economy will right itself? In this instance, “longer-term” may not be years, as was the case in the 2008/09 financial crisis, but may be by the end of this year. Truist disclosed that it had established a “Scenario Committee” to evaluate forecasting models and other macro uncertainties as part of its procedures for establishing the ACL under CECL. As summarized by US Bancorp in its first quarter 2020 earnings release: “Expected loss estimates consider both the decrease in economic activity and the mitigating effects of government stimulus and industrywide loan modification efforts designed to limit long-term effects of the pandemic event.”

Most noteworthy is the significantly increased magnitude of first-quarter 2020 provisioning compared to past trends and management mentions that CECL had an impact. Among the larger entities analyzed, first-quarter provisions were all well in excess of that reported in the fourth quarter of 2019 and generally ranged from 3× to 6×. US Bancorp reported the lowest increase at 2.5×, while at the higher end, State Street’s increase was 10× and Morgan Stanley’s was about 12×, in part because of the smaller relative size of their credit activities. Bank NY Mellon reported more complex activity than others, as its ACL increased 52% from $216 million at 2019 year-end to $329 million at the end of first quarter 2020. In the fourth quarter of 2019, it had an $(8) million provision reversal followed by a $(55) million adoption reduction of its ACL, before a $169 million first-quarter 2020 provision. At 2019 year-end, its ACL was allocated $122 million for outstanding loans and $94 million for unfunded commitments, which was a comparatively large ratio. After the first-quarter 2020 activity, its ending ACL was allocated $140 million for outstanding loans, $148 million for unfunded commitments, and $41 million for a new “other” category to address an array of other financial instruments, including federal funds sold, securities purchased under resale agreements, accounts receivable, and interest-bearing deposits with banks.

The smaller entities surveyed reported a pattern of even more dramatic increases. Bank of the Ozarks’ first-quarter 2020 adoption triggered a $94 million increase to its $109 million 2019 year-end ACL, which included establishing a new $55 million reserve for unfunded commitments, and further first-quarter 2020 provisioning of $118 million, which included $23 million for unfunded commitments, raising the ACL to $316 million, nearly a threefold overall increase. Trustmark, which had reported three years of provision reversals, experienced a first-quarter 2020 adoption charge of $26.6 million but disclosed that it actually had a decrease of $3.0 million for loans outstanding and a $29.6 million charge for a new ACL established for off-balance sheet credit exposures. It then reported a first-quarter 2020 provision for loans of $20.6 million compared to $3.7 million in the fourth quarter of 2019 and an additional $6.8 million for off-balance sheet credit exposure. In several instances, management made distinctions that a portion of the significant first-quarter 2020 provisioning reflected an effort to “build the reserve” not just to cover routine losses (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2

Selected Commentary about Allowances for Credit Losses in Q1 2020

JPMorgan Chase: “Given the likelihood of a fairly severe recession, it was necessary to build credit reserves.”

Bank of America: “1Q20 included a reserve build of $3.6 billion, due primarily to deteriorating economic outlook related to COVID-19.”

Washington Federal: “We remain cautious given the economic impacts of the pandemic … an outsized credit provision …we have not seen significant deterioration in asset quality metrics.”

Ally Financial: “Provision for loan losses increased … due to reserve build, primarily driven by forecasted macroeconomic changes associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Capital One: “Provision for credit losses … $5.9 billion … $3.6 billion [for] reserve build.”

Bank of the Ozarks: “If future economic conditions align with our projections, then our provision expense in future quarters should primarily …reflect … loan growth.”

In first-quarter 2020 reports, management teams generally discussed matters relating to COVID-19, especially regarding the uncertainty it represents. For example, Wells Fargo noted that: “The increase in the ACL for loans reflects forecasted credit deterioration due to the COVID-19 pandemic and credit weakness in the oil and gas portfolio due to the recent sharp declines in oil prices.” Ally Financial reported a $903 million provision and pointed out: “Our qualitatively determined allowance associated with the deterioration in the macroeconomic outlook from COVID-19 resulted in $602 million of additional provision expense for credit losses.” [emphasis added]

Among many efforts at disclosing important information, the following examples highlight the type of innovative disclosures found in first-quarter 2020 earnings information: BancorpSouth, which reported a $46 million provision compared to no provision in the fourth quarter of 2019, presented a chart of “COVID-19 High Risk Portfolios,” breaking out balances outstanding and committed amounts for the medical, hotels and accommodation, retail commercial real estate, food services, and oil and gas sectors that represented 15.57% of its total lending portfolio, and then further detailing the subcomponents of each, such as medical clinics and nursing homes. Ally Financial presented a “customer deferral summary” that highlighted the number of accounts requesting deferral and noted that 76% had not obtained prior extensions, revealing the payment stresses developing among consumers and its efforts to work with its customers. Trustmark similarly presented details on “COVID-19 Impacted Industries” and “Loan Customer Assistance Programs.” United Bankshares provided details regarding its participation in the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP).

That the CECL estimating effort in the first quarter of 2020 had incredible stresses and conflicting insight was captured by the Wall Street Journal on April 15, 2020: “[JPMorgan] said the provision was based, in part, on the assumption that U.S. gross domestic profit [Q2] would fall an annualized 25% and unemployment would rise to more than 10% in the second quarter. But JPMorgan economists have recently amended their forecast to a 40% decline in GDP in the quarter and a 20% unemployment rate (“JP Morgan, Wells Prep for Fallout,” p. A8). This worsening economic forecast was released on April 9, 2020, just five days before JPMorgan’s earnings release.

The Illusion of Certainty

The estimation process required by CECL must incorporate two very uncertain variables. First, how is the credit portfolio, as it exists at a point in time, going to react to the forecasted economic environment—essentially, how applicable are past historical data and experience? Second, how reliable is the macroeconomic forecasting model? The interaction of these two dimensions compounds the uncertainty involved. As the Bank of the Ozarks noted, per Exhibit 2, “If future economic conditions align with our projections.” [emphasis added] Inherently, that “if” represents a very uncertain proposition.

Because the COVID-19 pandemic’s consequences are unknown and very variable, and since government responses and their effectiveness are also very variable, the potential evolution of the macroeconomic environment is extremely uncertain. The situation is akin to the “fog of war” concept proffered by Carl von Clausewitz: “Three quarters of the factors on which action in war is based are wrapped in a fog of greater or lesser uncertainty.” (On War, 1832) As a perfect example, recent data released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (as reported by CNBC) evidenced a drastic deviation from forecasts by Wall Street economists–in May, it reported a 2.5 million gain in jobs which was much, much better than the consensus among economists of a loss of 8.3 million jobs; in June, it reported a 4.8 million gain in jobs, which was again much better than the 2.9 million consensus forecast. These types of disparities and uncertainties will have to be evaluated as management teams prepare their CECL analyses for second quarter 2020 reporting.

Because the COVID-19 pandemic’s consequences are unknown and very variable, and since government responses and their effectiveness are also very variable, the potential evolution of the macroeconomic environment is extremely uncertain.

Financial statements are presented with the appearance of a numerical precision that often does not, and cannot, exist. Inferring such precision is illusory, especially with regard to the estimates required by CECL. For example, Ally Financial’s disclosure that $602 million of its large $903 million first quarter 2020 credit loss provision (fully two-thirds of the total) reflected management’s qualitative judgment serves as evidence of the significant uncertainty management felt regarding the modeling process. When one considers the underlying uncertainties of the modeling process and the pandemic environment, it is highly unlikely that the data and management judgment could actually be distilled down to such precision, and the same would be true for efforts by the other entities. By convention, however, these estimates are often interpreted as if they represent greater certainty than can really exist.

The CECL Difference

At this time of unprecedented economic uncertainty in the midst of a public health crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, management teams have universally recorded credit loss provisions in the first quarter of 2020 substantially higher than they would have recorded under the prior “incurred loss” accounting model. This conclusion is inherently obvious, not just by the comparative magnitude of the loss provisioning, but because the losses, while foreseeable, have not yet been incurred. The major indicators that losses have been or are being incurred are relatively stable, such as levels of nonperforming loans and past due status of consumer loans (an especially difficult measurement when banks are offering waivers), and several entities reported that they were increasing the provisioning for unfunded commitments. The “incurred” model required ACL provisioning for an unfunded commitment if it was specifically obvious that in a particular situation it will be extended into a loss situation—the proverbial “throwing good money after bad.” But generally, such overall unfunded exposures would not meet that identifiable criterion. Under the CECL model with its use of analytics, forecasting, and historical experience, greater provisioning for unfunded commitments would be expected. From a review of the disclosures, such increased provisioning did occur and in some instances were newly established ACLs or dramatically higher.

These are not the types of statistics that would generate first-quarter 2020 credit loss provisioning levels of five to ten times greater than those reported in the fourth quarter of 2019 under the prior “incurred loss” accounting model. Furthermore, the new CECL requirements caused a major shift for those entities that had been reporting provisioning reversals.

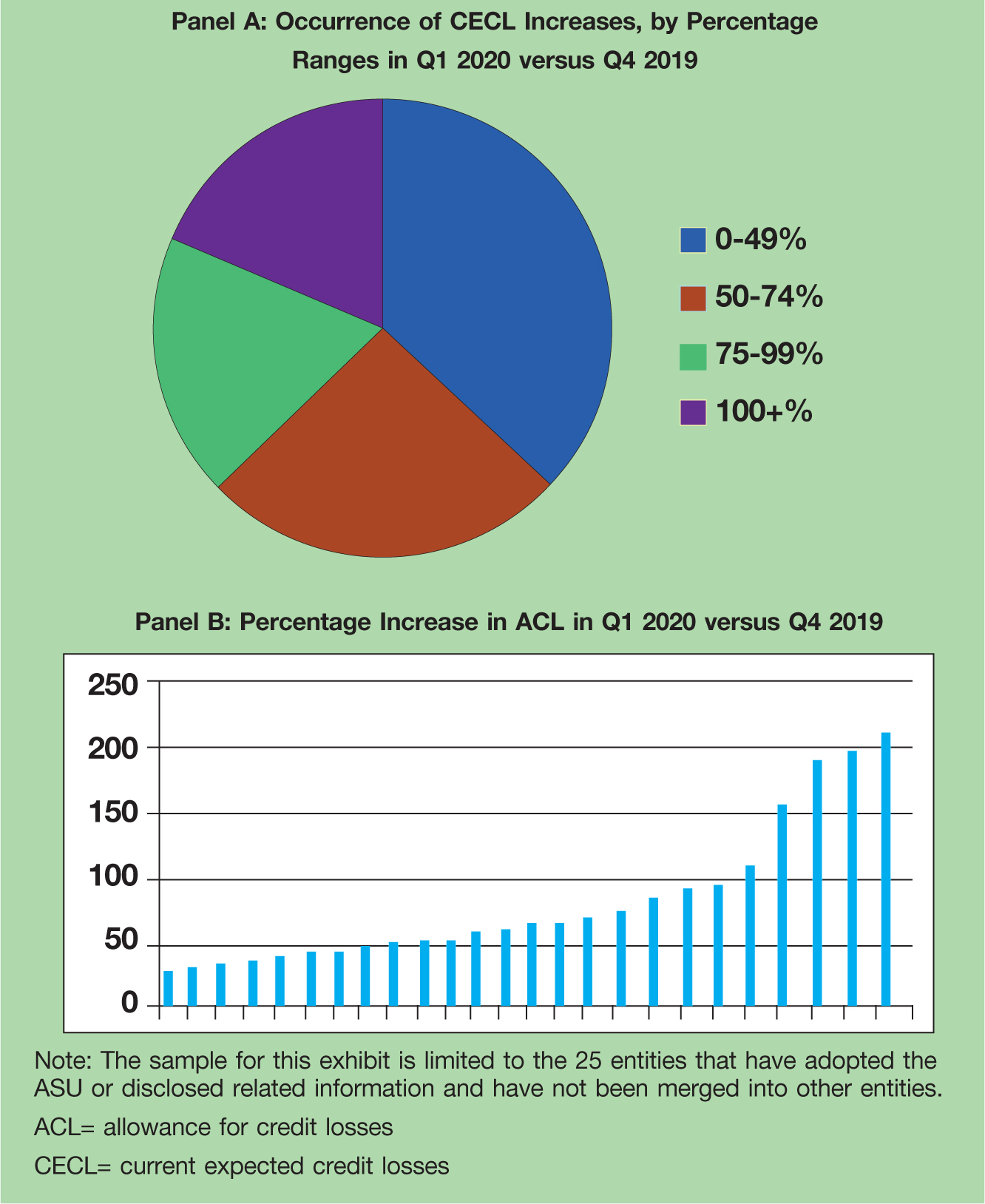

In summary, CECL has made a profound difference in loss recognition estimation. The increase in ACL levels from December 31, 2019, under the incurred loss model to March 31, 2020, under the CECL model has been dramatic. Exhibit 3 summarizes the magnitude of that increase for the sampled entities. (Not included are entities that did not adopt CECL or disclose its impact, or entities that were acquired.) The smallest increases, in the 15–20% range, were by Wells Fargo, Bank of Hawaii, and Flagstar; the largest increases, in the 200% range, were by Bank of the Ozarks (which included a large increase for unfunded commitments), Sterling, and Truist (which may have been affected by acquisition activity). Time will tell how the particular evolution of economic duress and recovery attributable to COVID-19 aligns with the necessary loss provisioning, but it surely indicates that the loss provisioning is being recognized much more quickly under the new CECL guidance.

Exhibit 3

Increase in ACL Levels from Incurred-Loss Model in 2019 to CECL Model in 2020

Arianna S. Pinello, PhD, CPA, CIA is an associate professor of accounting in the Lutgert College of Business at Florida Gulf Coast University, Fort Myers.

Ernest Lee Puschaver, CPA specialized in audits of large banks during a 28-year career with PricewaterhouseCoopers, and subsequently held executive finance positions with FleetBoston (acquired by Bank of America) and the Federal Home Loan Bank of Atlanta.