This article, "The Tangle of Intangible Assets and Business Combinations," originally appeared on CPAJournal.com.

Summary provided by MaterialAccounting.com: The article below addresses concerns related to intangible assets and business combinations as well as FASB’s possible direction of future standards.

In Brief

Since January 2014, FASB has issued several significant pronouncements on business combinations and intangible assets; however, the interaction between the two remains complex, leading to several related questions and concerns: What is the current practice of recognition and measurement for intangible assets in a business combination? Why is the issue causing such an endless array of standards? Where do we go from here? This article first addresses these concerns, then examines FASB’s current projects and agenda items to consider the possible direction of future standards on this topic.

***

In January 2014, FASB issued Accounting Standards Update (ASU) 2014-02, Intangibles—Goodwill and Other (Topic 350): Accounting for Goodwill. Before the end of 2014, two more updates on the topic of business combinations were issued: ASU 2014-17, Business Combinations (Topic 805): Pushdown Accounting(November 2014); and ASU 2014-18, Business Combinations (Topic 805): Accounting for Identifiable Intangible Assets in a Business Combination(December 2014). In 2015, another two updates follow up on this issue: ASU 2015-05, Intangibles—Goodwill and Other (Topic 350): Internal-Use Software (April 2015); and ASU 2015-08, Business Combi nations (Topic 805): Pushdown Accounting—Amendments to SEC Paragraphs Pursuant to Staff Accounting Bulletin No. 115 (May 2015). Together, these standards represent additional episodes to the ongoing saga between intangible assets and business combinations.

The interaction between intangible assets and business combinations is so entangled because a business combination is a unique type of accounting transaction that allows some previously unrecorded economic benefits to be reflected on the financial statements for the first time, often as intangible assets. Upon a business combination, the acquiree’s internally developed intangible assets are recognized and carried on the acquirer’s balance sheet, including separately identifiable intangible assets (e.g., patents, customer lists) and goodwill. A business combination is the only accounting transaction that gives rise to goodwill carried on the balance sheet (referred to as “accounting goodwill”). In a sense, this entanglement was acknowledged as far back as 2001, when FASB issued SFASs 141, Business Combinations, and 142, Goodwill and Other Intangible Assets. It has been more than a decade since the first issuance of the twin set of standards, and several revisions, supersessions, and codifications have been released since then.

Intangible Assets in the ASC

To sum up the changes over more than a decade, one of the most important developments since the issuance of SFAS 141 and SFAS 142 is the FASB Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) of 2009, which organized all of U.S. GAAP into a single source. Since then, FASB has issued ASUs to communicate changes to the ASC. Under the ASC, accounting standards are grouped by topics, and a master glossary consolidates the definitions of accounting items. Guidance on intangible assets is grouped under Assets (Topic 350, “Intangible—Goodwill and Other”), while guidance on business combinations is grouped under Broad Transactions (Topic 805, “Business Combinations”). Though the two topics do not at first seem so entangled, a closer look at ASC Topic 350 reveals their complex connection.

The interaction between intangible assets and business combinations is so entangled because a business combination is a unique type of accounting transaction.

ASC Topic 350 “provides guidance on financial accounting and reporting related to goodwill and other intangibles, other than the accounting at acquisition for goodwill and other intangibles acquired in a business combination” (ASC 350-10-05-1). For that matter, guidance for intangible assets acquired in a business combination is provided in ASC 805-20. This confirms that intangibles acquired in a business combination are to be accounted for differently from other intangibles. When it comes to accounting for intangible assets, it is important to ascertain what the situation calls for.

ASC 805-20 covers all identifiable assets and liabilities acquired in a business combination, not just intangibles. Yet, while tangible assets and liabilities are easy to identify and value, the process is usually less straightforward with intangibles. The ASC Master Glossary simply defines intangible assets as assets (other than goodwill) that lack physical substance, whereas assets are defined as probable future economic benefits obtained as a result of past transactions (Concept Statement 6). Identifiable assets must also be capable of being separate from the business or must arise from a contractual or other legal right owned by the entity. Identifying assets that meet these criteria can be a difficult process, requiring in-depth knowledge of the operations of the acquired company.

Other than separately identifiable intangibles, there is also the unidentifiable intangible—accounting goodwill, under ASC 805-30. The Master Glossary defines accounting goodwill as “an asset representing the future economic benefits arising from other assets acquired in a business combination that are not individually identified and separately recognized.” Similar to identifiable intangibles, the definition of accounting goodwill is rather established and stabilized. In practice, goodwill is calculated as the purchase price paid above and beyond the fair value of net assets acquired in a business combination. To this extent, the definitions of intangibles—both for separately identifiable intangibles and accounting goodwill—have stabilized in the past decade.

Identifying Intangibles

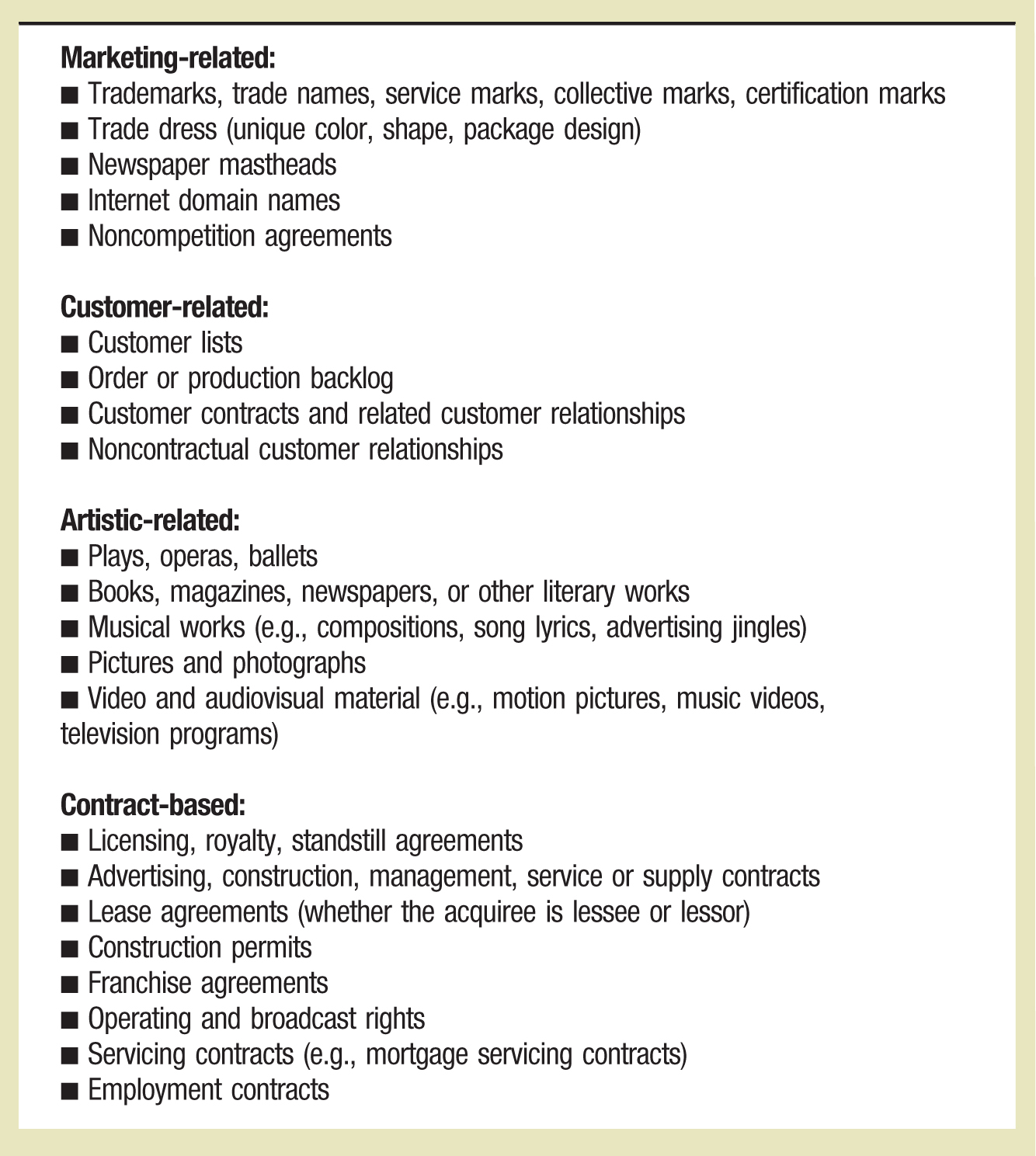

ASC 805-20-55-13 gives a non-exhaustive list of examples of intangibles often encountered in business combinations (reproduced in the Exhibit). Beyond this list, the acquirer in a business combination has the discretion to identify as intangible assets any probable future economic benefits that lack physical substance.

EXHIBIT

Examples of Intangible Assets That Are Separately Identifiable

ASC 805-20-25-10 offers specific guidance on identifying intangible assets: to be identified separately on the balance sheet, an intangible asset acquired in a business combination must first meet the general definition of an asset. ASC 805-20-25-2 refers directly to the definition of assets given in Concept Statement 6. ASC 805-20-25-3 reflects the concept of “future economic benefits obtained as a result of past transactions,” and requires that intangibles separately identified must be part of what the acquirer and the acquiree exchanged in the business combination, rather than the result of separate transactions.

In addition, ASC 805-20-25-10 points out that an asset is separately identifiable if it meets either one of two criteria:

- The intangible asset is separable—that is, capable of being separated or divided from the entity and sold, transferred, licensed, rented, or exchanged, regardless of whether the entity intends to do so.

- The potential future economic benefit of the asset arises from contractual or other legal rights, regardless of whether those rights are transferable or separable from the entity.

In sum, identifiability for intangible assets requires the satisfaction of either the separability criterion or the contractual-legal criterion.

The value of acquired intangible assets that are not separately identifiable as of the acquisition date should be subsumed into goodwill. In the implementation guidance, ASC 805-20-55-6 gives an example of a non-identifiable intangible: an assembled workforce acquired in a business combination. Because an assembled workforce cannot be sold or transferred separately from the other assets in the business, any value attributed to it is subsumed into goodwill.

The process of identifying intangibles acquired in business combination involves a due diligence review of the acquired company to obtain an understanding of the business and the resources it depends upon to generate profits. The idea is to identify the resources that are likely to be the primary sources of the company’s cash flows in the future. The primary driver of value in the entity depends upon the nature of the business. For example, in the food and beverage business, the main driver of value is most likely marketing-related assets, such as a brand name or trademark. For some technology companies, however, profit is generated via contract-related assets, such as licensing or royalty contracts on products or processes owned by other companies. The next step is to identify secondary resources that generate revenue for the business, either in conjunction with primary resources or as stand-alone revenue-generating assets.

A thorough review of the acquiree’s business, including historical and prospective financial information, is an important step in the process. A commercial analysis of the enterprise should provide some understanding of the importance of branding and other marketing strategies used by the company. Such an analysis usually involves a review of the customer base, any licensing or royalty agreements, the value of any operating lease contracts, and any industry-specific intangibles. It is also important to discuss these issues with management on both sides of the deal and review the purchase agreement. Parties to the transaction are considered an important source in identifying potential intangible assets.

Measuring Intangible Assets

Despite the clear guidance on the definition and identification criteria for intangible assets acquired in a business combination, accounting for the assets remains challenging in practice because of measurement issues. Measurement is governed by ASC 805-20-30, which is short and to the point: for assets and liabilities acquired in a business combination, the initial measurement basis is the acquisition-date fair value. The Master Glossary defines fair value as the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date. In other words, fair value is the exit price that a market participant would be willing to accept upon sale of the intangible asset.

ASC Topic 820, “Fair Value Measurements and Disclosures,” provides guidance on the three approaches used to determine fair value: the market approach, the cost approach, and the income approach. The market approach (ASC 820-10-55-3A) uses prices from market transactions involving similar assets to value intangibles. Used for assets that are actively traded, the market approach relies on multiples computed by reference to comparable sales of a similar asset. Intangible assets are typically unique in nature and are often not sold in active markets. When they are for sale, it is usually in conjunction with other components of the business. Because market data would not be available for such assets, this approach is seldom used.

The cost approach (ASC 820-10-55-3B to 3D) uses replacement cost as the valuation for an asset, assuming a market participant would not pay more for the asset than it cost to acquire or to construct a substitute asset of comparable utility. The cost method is appropriate to use only for assets that are accounted for via production costs, which is not applicable to most intangible assets. It is also appropriate for valuation of certain assets that may be used in conjunction with intangible assets, such as internally developed software and the content of an assembled workforce. These are assets for which replacement costs would usually be available during the valuation process.

The most commonly used approach for valuing intangible assets purchased in a business combination is the income approach (ASC 820-10-55-3F), which converts future amounts to be derived from the asset to a single current or present value using a discount rate. The excess earnings method, a common application of the income approach, is most often used to evaluate the intangible asset that represents the primary earnings driver of the business—for example, customer relationships or technology. The purpose of this method is to estimate the net earnings attributable to that asset alone. It starts with a forecast of net income that could be obtained from the asset over its remaining economic life. A charge is made against that net income for the fair value of the assets used in conjunction with the intangible (i.e., contributory assets). For example, customer lists might be useful to the enterprise only in connection with the infrastructure of the business used in the process of servicing customers. When valuing customer lists, property and equipment and working capital might be contributory assets that allow the company to benefit from the customer lists. In this case, the fair value of property and equipment and working capital would be deducted from net income forecasted to be attributable to customer relationships. Net income remaining after the charges for contributory assets represents excess earnings assumed to be generated by the intangible asset being valued. A discount rate is applied to the excess earnings stream in order to determine the asset’s fair value. The discount rate should be based upon the risk profile of the underlying asset.

Measurement of accounting goodwill in a business combination.

ASC Topic 805-30-30-1 governs the initial accounting for goodwill. Accounting goodwill is first measured as the residual of the purchase price after subtracting amounts assigned to identifiable assets and other components of the transaction. (Components of the transaction other than assets or liabilities include any non-controlling interests or any interest in the acquiree held by the acquirer prior to the business combination; these components fall beyond the scope of this article.) If the residual is negative, a gain from a bargain purchase may be recognized. The guidance requires a full reassessment of the purchase price allocation in order to ensure that all assets and liabilities are properly recognized before recording a gain from a bargain purchase.

Private company stakeholders indicated that the cost of the required annual impairment test for goodwill outweighed its benefits for private companies.

Subsequent accounting for intangible assets.

After the identification and initial measurement of intangible assets in a business combination, only the issue of subsequent measurement remains—that is, how intangible assets are valued in periods subsequent to the acquisition date. After a business combination, acquired assets are accounted for in accordance with ASC Topic 350, “Intangibles—Goodwill and Other.” Finite-life intangibles are to be amortized over the economic life, whereas infinite-life assets are not amortized, but assessed for impairment on an annual basis. If it is determined that the carrying value of an asset is higher than its fair value and the drop in fair value is not recoverable, an impairment loss should be recognized and the asset basis written down to fair value.

ASC 350-20-35-1 indicates that goodwill is not to be subsequently amortized, but should be tested for impairment at least annually. In ASU 2011-08, Intangibles—Goodwill and Other (Topic 350): Testing Goodwill for Impairment, FASB allows an optional qualitative impairment test; the reporting entity may choose to perform a qualitative test to determine whether a quantitative test is necessary, or it may skip the qualitative test and proceed directly to the quantitative test. Any impairment loss indicated by the quantitative test is to be recognized immediately. This general annual impairment test rule for accounting goodwill is further updated by ASU 2014-02, which provides an accounting alternative for private companies (see “The Continuing Evolution of Accounting Alternatives for Private Companies” on page 48).

Newly Issued FASB Updates

ASUs issued in 2014 and 2015 add to the entanglement of business combinations and intangible assets recognition and measurement.

Amortization of goodwill by private companies.

ASU 2014-02 provides that private companies may elect to amortize goodwill over 10 years or less if the entity demonstrates that another useful life is more appropriate. If elected, amortization accounting should be applied prospectively to goodwill existing as of the beginning of the adoption year and new goodwill recognized in periods beginning after December 15, 2014. Private companies that make this election must also test goodwill for impairment based on a triggering event that suggests the fair value may be less than its carrying value. This guidance was issued because private company stakeholders indicated that the cost of the required annual impairment test for goodwill outweighed its benefits for private companies.

Pushdown accounting.

ASC 350-30-35-1 states that an intangible asset with a finite useful life should be amortized over its useful life to the reporting entity. This simple rule is well established for subsequent measurement of intangibles. Given the different bases carried on the acquirer’s books (fair value as of the acquisition date) and the acquiree’s separate books (amortized historical costs), however, amortization subsequent to the acquisition creates a discrepancy in the two sets of books and imposes difficulties for consolidated financial statements.

In ASU 2014-17, issued in November 2014, “pushdown accounting” refers to the accounting treatment that allows an acquiree to use the acquirer’s bases in the preparation of the acquiree’s separate financial statements. This update provides an accounting alternative to streamline the books between the acquirer and the acquiree.

ASU 2014-17 provides the acquiree with the option to apply pushdown accounting in its separate financial statements when the acquirer obtains control of the acquiree. In other words, if this option is elected, the acquiree would reflect in its separate financial statements the new bases of assets and liabilities as carried on the acquirer’s books. This ASU also allows for goodwill to be recognized on the acquiree’s books in a business combination—a major change to accounting standards! For the first time, an acquired entity is able to recognize internally generated intangibles, as well as accounting goodwill, as assets on its balance sheet. But if the acquirer has recognized a gain from a bargain purchase, the acquiree does not recognize a gain in its income statement under ASU 2014-17; instead, the acquiree reflects this gain as an adjustment to additional paid-in capital. This update applies to both public and private entities, as well as to not-for-profit organizations. Issued in May 2015, ASU 2015-08 gives further guidance on pushdown accounting, mainly to streamline the language with SEC paragraphs pursuant to pushdown accounting given in Staff Accounting Bulletin No. 115. This ASU made no substantive change in the treatment of pushdown accounting.

Identification of intangible assets by private companies.

With ASU 2014-18 (issued December 2014), private companies are no longer required to recognize separately from goodwill noncompetition agreements and customer-related intangibles incapable of being sold or licensed independently of the other assets in the business. Both noncompetition agreements and customer-related intangibles are included in the examples of separately identifiable intangibles for public companies under ASC 805-20-55-13 (see the Exhibit). ASU 2014-18 allows private companies to recognize fewer identifiable intangibles and more goodwill. This alternative is provided to reduce the cost and complexity of measuring intangible assets for private companies. ASU 2014-18 is effective for transactions occurring in fiscal periods beginning after December 15, 2015, though early adoption is permitted.

Private companies that elect not to recognize customer-related intangibles and noncompetition agreements separately from goodwill under ASU 2014-18 must also adopt the alternative treatment for goodwill under ASU 2014-02 and amortize it over 10 years or less; however, a private company that elects to amortize goodwill under ASU 2014-02 is not required to forego separate recognition of customer-related intangibles and noncompetition agreements under ASU 2014-18.

Customer’s accounting for fees in a cloud computing arrangement.

ASU 2015-05 (issued in April 2015) gives guidance on the accounting treatment of cloud computing arrangements. The key is whether the computing arrangement includes a software license. If a cloud computing arrangement includes a software license, then the customer should account for the software license element of the arrangement consistent with the acquisition of other software licenses. If a cloud computing arrangement does not include a software license, the customer should account for the arrangement as a service contract. The intended accounting effect is that all software licenses within the scope of Subtopic 350-40 (internal-use software) be accounted for consistent with other licenses of intangible assets.

Current FASB Projects

As of early November 2015, several projects on FASB’s agenda concerning the accounting for intangible assets and business combinations deserve a close watch. The focus appears to be on simplification; all projects concerning goodwill and intangible assets on the agenda fit into the Board’s simplification initiative.

Goodwill subsequent measurement.

After more than a decade of requiring no amortization and complex goodwill impairment tests for both public and private entities, ASU 2014-02 opens the door for private companies by permitting the amortization of goodwill. FASB is now considering the same change for public companies. In November 2013, the board added a project related to accounting for goodwill for public business entities and not-for-profit entities to its agenda. It aims to reduce the cost and complexity of the subsequent accounting for goodwill for publicly owned businesses.

In November 2014, FASB discussed additional research on the subsequent measurement of goodwill, including the IASB’s post-implementation review of its standards on business combinations; however, it did not make any decisions on this topic and instead directed the staff to perform additional research on 1) identifying the most appropriate useful life if goodwill were to be amortized and 2) simplifying the goodwill impairment test. In 2015, two projects were added to FASB’s agenda on this topic.

The first project, Subsequent Accounting for Goodwill for Public Business Entities and Not-for-Profit Entities, evaluates whether additional changes need to be made to the procedure for subsequent accounting for goodwill. The second project, Accounting for Goodwill Impairment, is aimed at reducing the cost and complexity of the goodwill impairment test. As of November 2015, FASB reached a tentative decision to proceed on both projects using a phased approach. The first phase is to simplify the impairment test by removing the requirement to perform a hypothetical purchase price allocation when the carrying value of a reporting unit exceeds its fair value (Step 2 of the impairment model in current GAAP). In the second phase, FASB plans to work concurrently with IASB to address any additional concerns about subsequent accounting for goodwill. Both projects are at the initial deliberation stage.

Accounting for identifiable intangible assets in a business combination.

At its November 2014 meeting, the Board added another project to its agenda: accounting for identifiable intangible assets in a business combination for public business entities and not-for-profit entities. This project evaluates whether certain intangible assets should be subsumed into goodwill, with the focus on customer relationships and noncompetition agreements. With ASU 2014-18, private companies are no longer required to identify separately from goodwill noncompetition agreements and customer intangibles that cannot be sold or licensed separately from other assets. FASB is now considering the applicability of this treatment to public and not-for-profit entities. In October 2015, FASB deferred any decisions about whether not-for-profit entities should be able to use the option available to private companies. However, it decided to continue engaging with the international community on this project. Once again, consideration of IASB’s activities is explicitly mentioned. This project is also at the initial deliberations stage.

An Ongoing Issue

After a decade’s evolution of accounting for intangible assets in a business combination, only one thing is clear: the issue is not yet settled. The definitions and identifying criteria of intangible assets and accounting goodwill have remained relatively stable; however, measurement concerns still pose a challenge, especially with respect to the definition of fair value. The negotiations surrounding a business combination are strictly a subjective exercise between an acquirer and acquiree. Yet, intangible assets, once separately identified, have to be measured objectively at fair value. Several measurement approaches are available to estimate fair value in the absence of an active market for the asset.

Subsequent treatment of accounting goodwill is also provoking considerable debates. It would seem that the profession is still searching for the most cost-efficient way to faithfully reflect this intangible asset in the financial statements. Private companies have been allowed to amortize goodwill and to use a simpler test for impairment, and FASB is considering expanding this treatment to public and not-for-profits entities. In addition, for the first time, an acquiree is allowed to reflect internally generated intangible assets and accounting goodwill on its balance sheet after a business combination by pushing down values carried on the acquirer’s book to its separate financial statements. The effect on the valuation of intangible assets will probably take years to ascertain.

The cost and complexity of the accounting treatments remain major concerns. From ASUs issued in 2014 and 2015 to the ongoing current projects, FASB’s objectives are to reduce complexity in cases where the benefit of the accounting treatment may not justify the cost of applying it. Specific issues, such as separate identification of customer-related intangibles and noncom-petition agreements, still need to withstand the test of cost-benefit efficiency for public and nonprofit entities.

More than a decade after SFAS 141 and 142 were initially issued, accounting treatment of intangible assets upon a business combination is taking shape; however, financial statement users have to keep in mind that fair value–based asset values are only estimates of probable future economic benefits. The valuation of intangible assets can be informative but never precise. Considerable judgment has to be exercised when analyzing financial statements with high amounts of intangible assets and goodwill. Business combination transactions only further obfuscate the accounting picture.

Kang Cheng, PhD is an associate professor of accounting at Morgan State University, Baltimore, Maryland.

Sharon Finney, PhD, CPA is an associate professor of accounting and chair of the department of accounting and finance, also at Morgan State University.